Disclaimer: This information is intended as general advice only and does not replace individual medical guidance. Consult your medical professional to determine the best approach for your specific needs.

Introduction

Hypermobility refers to joints that move beyond the typical range—sometimes described as being “double-jointed.” Joint hypermobility is relatively common, especially in children, women, and individuals of Asian, Middle Eastern, or African descent. It is estimated that 10–20% of the general population may exhibit joint hypermobility, though this can vary widely by age, gender, and ethnicity.

But Why Are People Hypermobile?

- Genetic Inheritance Affecting Collagen and Connective Tissue:

- Collagen is like the body’s scaffolding. It helps hold tissues together and provides stability and support to joints, skin, blood vessels, ligaments, and internal organs. In people with hypermobility, there is a higher percentage of type III collagen (naturally occurring stretchy type) and less type I collagen (the firmer, less stretchy type).

- Stretching and Repetitive Positions:

- Repetitive positioning and stretching of ligaments and muscles can increase the flexibility of the ranges of the joints.

Is Hypermobility A Medical Condition?

On its own, joint hypermobility is not considered a medical condition. It can even be an advantage in activities like dance, yoga, rock climbing, swimming, tennis, or gymnastics.

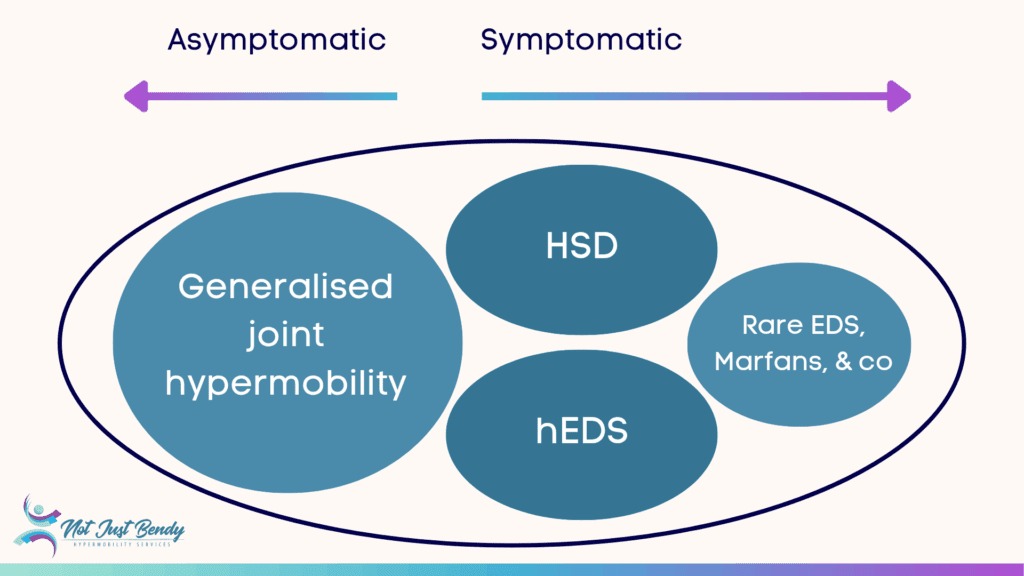

Individuals who are hypermobile but do not have any related musculoskeletal issues can be defined as Asymptomatic Generalised Joint Hypermobility (A-GJH).

However, for other individuals, hypermobility may be accompanied by pain, fatigue, frequent injuries, or other systemic symptoms that affect daily life.

In such cases, a medical diagnosis may be considered under Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (HSD), or Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), both of which involve symptomatic hypermobility but differ in diagnostic criteria and classification.

What’s the Difference between EDS, hEDS, and HSD?

Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of heritable connective tissue disorders. There are currently 13 recognised subtypes, each involving a genetic variation that affects the structure or processing of collagen or collagen-related proteins, essential for the strength and flexibility of skin, joints, blood vessels, and organs. EDS symptoms and severity vary by subtype but may include joint instability, fragile or stretchy skin, easy bruising, poor wound healing, and—in rare types—vascular or organ fragility.

- Learn more about What Is EDS from the EDS Society

- Access the EDS GP Toolkit to share the information with your General Practitioner

Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS)

Hypermobile EDS (hEDS) is the most common and best-known subtype of EDS. Although its exact prevalence is unknown, it is no longer considered as rare as previously thought and is believed to be underdiagnosed.

Unlike other EDS subtypes, there is currently no known genetic marker for hEDS. Diagnosis is based on a detailed set of clinical criteria, including generalised joint hypermobility, a history of musculoskeletal issues, specific features of skin/cardiac/skeletal systems, and often a family history of similar traits. The diagnostic criteria for hEDS were updated in 2017 to improve clarity for clinical and research efforts, with a planned revision expected in 2026-2027.

hEDS can affect every part of the body and best practice management typically involves a multidisciplinary team (including multiple allied health and medical specialists). Symptoms may fluctuate over time and often overlap with other conditions like Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) or Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS).

It is important to understand that according to the international guidelines, diagnosis of hEDS is only recommended in adults, or once an individual has reached skeletal maturity.

In children and adolescents, a diagnosis of generalised joint hypermobility (GJH) or hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) may be more appropriate, as signs and symptoms of hEDS can evolve over time and skeletal maturity has not yet been reached (Tofts et al., 2023). According to the 2017 diagnostic framework, the diagnosis of hEDS should be deferred until after the age of 18, or until skeletal maturity is confirmed, to reduce the risk of misdiagnosis during growth (Malfait et al., 2017).

- Learn more about hEDS diagnosis from the EDS Society

- Access the hEDS Diagnostic Checklist from the EDS Society

- Read the latest research publication on Hypermobility Diagnosis in Children (Tofts et al., 2023)

- Read the research publication on the 2017 International Classification of EDS (Malfait et al., 2017)

Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (HSD)

HSD is a group of diagnoses applied when a person has evidence of hypermobility (current or historical), alongside significant musculoskeletal symptoms. There are several subtypes of HSD:

- Generalised HSD (G-HSD): Multiple joints are currently hypermobile.

- Historical HSD (H-HSD): Joints were hypermobile in the past, but not currently.

- Localised HSD (L-HSD): Hypermobile in only one joint or region.

- Peripheral HSD (P-HSD): Hypermobility limited to the hands and feet.

HSD is related to hypermobility but does not meet the strict diagnostic criteria for hEDS. However, individuals with HSD can still experience significant symptoms such as pain, joint instability, fatigue, autonomic symptoms (e.g., dizziness, palpitations), digestive or bladder issues, and reduced quality of life.

It is important to understand that the symptoms of HSD and hEDS can be identical. HSD is no more or less severe than hEDS. Although HSD is not classified as a genetic disorder, the impact on an individual’s physical and emotional health can be just as significant as hEDS. HSD is a real, diagnosable,and treatable condition—it deserves the same level of care and attention as other connective tissue conditions.

- Learn more about HSD from the EDS society

What Conditions Are Associated With HSD/hEDS?

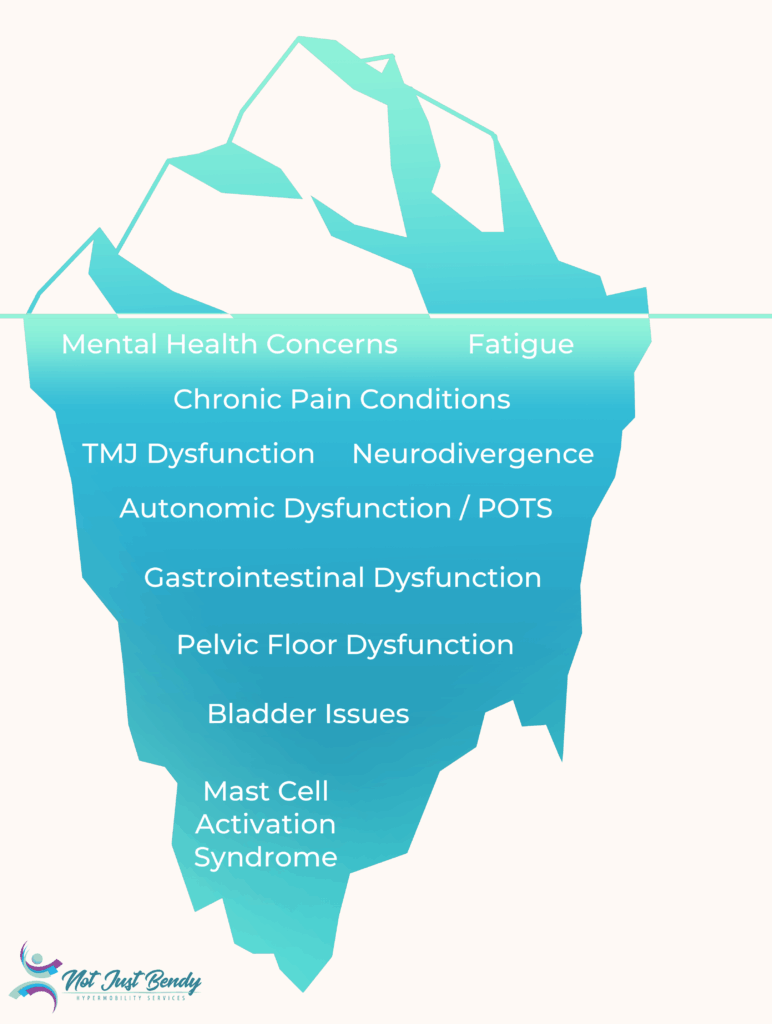

Hypermobility is not just about flexibility. For some individuals, it can be associated with a wide range of symptoms affecting multiple body systems.

Individuals with hypermobility often experience associated conditions that further complicate their symptom burden. Everyone’s presentation is unique. Some may experience none of these conditions, while others may experience several. The severity of symptoms also varies.

The reasons for the conditions occurring more commonly in HSD/hEDS are still being researched. However, because connective tissue is found throughout the entire body, its dysfunction can affect a variety of organ systems.

The iceberg is a powerful metaphor used to illustrate the nature of HSD/hEDS. Just like an iceberg, only a small portion of the condition is visible on the surface—usually the hypermobility or joint laxity that others can see. However, most challenges lie hidden beneath the surface.

Because these symptoms are not immediately visible to others, individuals may look “normal” on the outside—while inside, they are managing a complex, multi-systemic condition. The iceberg helps clinicians, family, and friends understand the hidden depth and burden of these disorders and highlights the importance of holistic care and support.

Common Co-Morbidities

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): A form of autonomic dysfunction causing rapid heart rate upon standing, dizziness, fatigue, brain fog, and exercise intolerance (Hakim et al., 2017).

- Learn more about POTS & Hypermobility

- Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS): Dysregulation of mast cells can lead to allergic-type symptoms (e.g. hives, flushing, swelling), gastrointestinal upset, food sensitivities, and systemic inflammation.

- Learn more about MCAS & Hypermobility

- Gastrointestinal Dysmotility & Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Constipation, diarrhoea, bloating, and nausea are often reported, due to altered gut motility and connective tissue laxity.

- Fatigue: Chronic fatigue is one of the most reported symptoms in individuals with HSD/hEDS. It can be both physical and mental, often unrelated to activity level or sleep quality.

- Factors contributing to fatigue include poor sleep due to pain or dysautonomia, inefficient muscle function due to joint instability, nervous system dysregulation, and comorbid conditions such as POTS, MCAS, or sleep disorders.

- A recent study suggests that fatigue can also be exacerbated by not recovering fully from COVID-19 in those with G-HSD (Eccles et al., 2024).

- Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dysfunction: Jaw pain, clicking, and dislocations are common due to joint laxity.

- Chronic Pain Conditions: Including myofascial pain, small fibre neuropathy, and central sensitisation syndromes.

- Pelvic Floor Dysfunction & Bladder Symptoms: Such as urinary incontinence, urgency, or pelvic organ prolapse, especially in women.

- Learn more about Women’s Health Issues & Hypermobility

- Neurodivergence (e.g. ADHD, Autism): Emerging research has shown a significant overlap with neurodevelopmental conditions (Nisticò et al., 2022)

- Mental Health Concerns: Anxiety, depression, and trauma-related symptoms may co-occur, either as part of the physiological picture or due to the challenges of living with a poorly understood chronic condition (Halverson et al., 2023).

Frequently Overlapping or Initial Diagnoses

Because symptoms of hypermobility can vary widely and overlap with many other conditions, delayed or partial diagnosis is unfortunately common. Many people with HSD or hEDS are initially diagnosed with other conditions that reflect only part of the clinical picture. These may include:

- Fibromyalgia – due to widespread pain, fatigue, and sensitivity, especially in older individuals who may no longer appear hypermobile on physical examination due to age, or long-term injuries.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome/ME/CFS – because of persistent exhaustion, brain fog, and post-exertional malaise, which can overlap with fatigue experienced in hypermobility-related disorders.

- Growing pains – in hypermobile children with joint discomfort, fatigue, and frequent injuries

- Somatisation disorders – when physical symptoms are incorrectly attributed to psychological causes due to the absence of obvious clinical findings.

- Anxiety or depression – when symptoms of dysautonomia (e.g., palpitations, dizziness, sweating) are misinterpreted as anxiety, or when the emotional toll of chronic, unmanaged symptoms is mistaken for the root cause.

- Functional Neurological Disorder (FND) –when neurological symptoms (such as tremors, non-epileptic seizures, or motor/sensory dysfunction) cannot be explained by structural abnormalities on imaging. These symptoms may occur in individuals with hypermobility and could relate to co-existing autonomic dysfunction, fatigue, or central sensitisation (Nisticò et al., 2022).

Who Can Officially Diagnose HSD/hEDS?

Your experienced allied health professional can assess you against the international criteria and offer you a provisional assessment.

An “official” diagnosis (e.g. needed for some government funding) requires exclusion of all other possibilities which requires a GP review and at times a referral to a rheumatologist, geneticist or other hypermobility aware medical specialist.

It is important to note that although official diagnosis can be validating, as there is no specific medical cure – focusing on management rather than diagnosis is recommended.

How Is Hypermobility Managed?

For effective management of HSD/hEDS, clinical guidelines focus on improving function, reducing symptoms, and preventing long-term complications. Management should be personalised, goal-directed, and ideally guided by a multidisciplinary team.

Management Strategies

- Enhance joint stability, coordination, and movement efficiency through individualised physiotherapy or exercise physiology programs.

- Find out more about How We Can Help & the Services We Offer At Not Just Bendy

- Learn more about physical therapy for hypermobility management in children, adolescents and adults (Engelbert et al., 2017)

- Pain & stiffness management, including a combination of massage/manual therapy, hydrotherapy, heat/cold treatments, braces/splinting/strapping, orthotics, medications or regenerative therapies like prolotherapy or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections etc.

- Improve proprioception and neuromuscular control to reduce injury risk

- Address associated conditions – ideally with health professionals who are familiar with hypermobility and connective tissue disorders — including:

- Gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., Gastroenterologist, Pelvic floor/health Physiotherapist, Dietician)

- Mast cell activation (e.g., Immunologist, Functional GP)

- POTS (e.g., GP, Electrophysiological Cardiologist, Exercise Physiologist or Physiotherapist with POTS expertise)

- Women’s Health Issues (e.g. Gynaecologist, Women’s Health Physiotherapist, Urologist, Gastroenterologist)

- Energy conservation and pacing techniques to manage fatigue and flares.

- Psychological support to cope with chronic pain, sensory issues and the emotional impact of living with a long-term condition (Psychologist, Psychiatrist, or mental health OT)

- Others –as everyone’s issues are unique everyone’s management and team will be different.

Multidisciplinary Team

Your General Practitioner (GP) is your first step in managing and co-ordinating your care. Just because you have HSD/hEDS does not mean you do not need to be screened for other health issues.

- Access the EDS GP Toolkit to kick start the discussion with your General Practitioner

A collaborative multidisciplinary approach, involving GP, physiotherapists, exercise physiologists, doctors, dietitians, psychologists, occupational therapists, and medical specialists etc.—is often the most effective way to help individuals manage their condition, build resilience, and support return to the meaningful activities.

While access to a multidisciplinary team with expertise in HSD/hEDS is ideal, the number of medical professionals with such knowledge is limited. Educating and upskilling your existing, willing healthcare professionals can be a highly effective strategy—both to enhance your own care and to help build broader understanding for others in the future.

Given the complex and multisystemic nature of HSD/hEDS, new providers may feel overwhelmed by the breadth of symptoms. Approaching each healthcare professional with a clear plan and specific goals can ensure their expertise is used effectively. Defining the purpose of their involvement helps you gain the most meaningful, targeted support from each member of your team.

- Find out more about How We Can Help & the Services We Offer At Not Just Bendy

How Can Not Just Bendy Help?

At Not Just Bendy, our team is highly experienced in managing hypermobility-related conditions. We understand the unique needs of individuals with HSD and hEDS and offer personalised care plans tailored to your goals and symptoms.

One of our core strengths is our strong industry connections and access to a wide multidisciplinary network. This allows us to support you in navigating the complexities of hypermobility and its related conditions, and to connect you with trusted professionals—including rheumatologists, geneticists, dietitians, and more—when further support is needed.

Our Physiotherapists Can:

- Perform detailed musculoskeletal assessments to identify contributing factors to pain, instability, and fatigue

- Provide a provisional diagnosis based on your clinical presentation, and work with your GP to coordinate any necessary investigations or referrals to confirm the diagnosis. This may include blood tests to rule out other causes or referral to a specialist for formal assessment.

- Provide real-time ultrasound imaging to assess and re-train weak or overactive muscles

- Develop targeted rehabilitation programs to support joint control, reduce injury risk, and manage energy use more efficiently

- Educate you about pacing, posture, ergonomics, and activity modification to manage both pain and fatigue

- Assist with symptom tracking (e.g., pain and fatigue diaries) and liaise with your broader healthcare team for integrated care

- Recognise when input from specialist or other healthcare professionals is needed, and facilitate referrals to clinicians experienced in hypermobility-related disorders

We believe that movement is medicine, but it must be approached in a way that respects your unique physiology and pacing needs.

This article has been compiled by the Not Just Bendy team based on current research and clinical experience in managing hypermobility.

Want some support figuring things out?

Check out the services we offer, learn how we can help, or get in touch to book a session with our therapists.

Learn More

You can find more information curated by Not Just Bendy at:

- What Is Hypermobility?

- Mast Cell Activation Disorders

- Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

- Exercise Tips for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS)

- Hypermobile Hips

- Women’s Health Issues In Hypermobility

- Switching on the Lightbulb to see Hypermobility Disorders

- Hypermobility Screening & Prevention

- Exercise Classes for Hypermobility

- Hypermobility Resources

- Hypermobility Brisbane Physiotherapy

References

- Tofts, L. J., Simmonds, J., Schwartz, S. B., Richheimer, R. M., O’Connor, C., Elias, E., Engelbert, R., Cleary, K., Tinkle, B. T., Kline, A. D., Hakim, A. J., Van Rossum, M. A. J., & Pacey, V. (2023). Pediatric joint hypermobility: a diagnostic framework and narrative review. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 18(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02717-2

- Malfait, F., Francomano, C., Byers, P., Belmont, J., Berglund, B., Black, J., Bloom, L., Bowen, J. M., Brady, A. F., Burrows, N. P., Castori, M., Cohen, H., Colombi, M., Demirdas, S., De Backer, J., De Paepe, A., Fournel‐Gigleux, S., Frank, M., Ghali, N., … Tinkle, B. (2017). The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31552

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/what-is-eds/

- Not Just Bendy Hypermobility Services – resources & links directory https://www.notjustbendy.com/links/

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (n.d.). What is HSD? https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/what-is-hsd/

- Patient. (n.d.). Hypermobility syndrome. https://patient.info/bones-joints-muscles/hypermobility-syndrome-leaflet

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (n.d.). GP toolkit: For Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and hypermobility spectrum disorders. https://gptoolkit.ehlers-danlos.org/

- Halverson, C. M. E., Penwell, H. L., & Francomano, C. A. (2023). Clinician-associated traumatization from difficult medical encounters: Results from a qualitative interview study on the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes. SSM – Qualitative Research in Health, 3, 100237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2023.100237

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (n.d.). Genetics and inheritance. https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/genetics-and-inheritance/#1674754174755-eb93d867-7a88

- Eccles, J. A., Cadar, D., Quadt, L., Hakim, A. J., Gall, N., Bowyer, V., Cheetham, N., Steves, C. J., Critchley, H. D., & Davies, K. A. (2024). Is joint hypermobility linked to self-reported non-recovery from COVID-19? Case–control evidence from the British COVID Symptom Study Biobank. BMJ Public Health, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjph-2023-000478

- Engelbert, R. H. H., Juul-Kristensen, B., Pacey, V., de Wandele, I., Smeenk, S., Woinarosky, N., Sabo, S., Scheper, M. C., Russek, L., & Simmonds, J. V. (2017). The evidence-based rationale for physical therapy treatment of children, adolescents, and adults diagnosed with joint hypermobility syndrome/hypermobile Ehlers Danlos syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part C, Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31545

- Not Just Bendy Hypermobility Services. (n.d.). Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS) and its relationship to hypermobility. https://www.notjustbendy.com/blog/mast-cell-activation-syndrome-mcas-and-its-relationship-to-hypermobility-2/

- Nisticò, V., Iacono, A., Goeta, D., Tedesco, R., Giordano, B., Faggioli, R., Priori, A., Gambini, O., & Demartini, B. (2022). Hypermobile spectrum disorders symptoms in patients with functional neurological disorders and autism spectrum disorders: A preliminary study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 943098. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.943098

- Hakim, A., O’Callaghan, C., De Wandele, I., Stiles, L., Pocinki, A., & Rowe, P. (2017). Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome—Hypermobile type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31543

- Castori, M., & Colombi, M. (2015). Generalized joint hypermobility, joint hypermobility syndrome and Ehlers‐Danlos syndrome, hypermobility type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 169(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31432

Want To Learn More From Sharon Hennessey About Hypermobility?

Sharon’s ground-breaking hypermobility educational courses through The Hypermobility Project are launching soon – sign up now to know when the courses go live!

Join the wait list to be the first to access exclusive video content, tailored for health professionals seeking to better understand hypermobility.